By Emilie Poletto-Lawson and Dr Hannah Grist

One of the three pillars underpinning the University of Bristol’s Vision and Strategy (2030) holds that at Bristol, “our education is shaped by the fact that we are a world-class research-intensive university. The link between research and teaching informs our taught courses, and is integral to research supervision.” Our Vision imagines a future where we attract and inspire students “from across the globe, with a distinctive education offering, innovative teaching and research-rich curriculum that enriches their university experience, careers and lives.” Our staff development offer for colleagues who teach and support learning at the University forms the “Cultivating Research-rich Education and Teaching Excellence (CREATE)” programme, further highlighting the connection between research and education at Bristol.

But what does it mean to cultivate a research-rich curriculum? What are some of the benefits and challenges, and how have colleagues at Bristol engaged with research-rich approaches?

Definitions and benefits of research-rich teaching

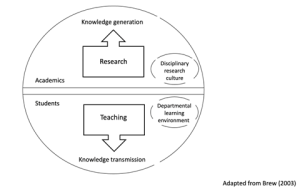

The traditional view of research and teaching in higher education – as schematised by Brew in 2003 – demonstrates a clear separation between the two. This could perhaps be seen as the origin of the three learning, teaching and research pathways in our institution.

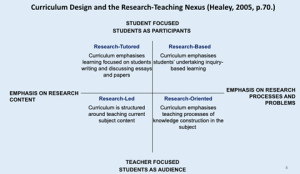

Two years later, Healey redefined the relationship between teaching and research in his seminal 2005 work, identifying four approaches to the research-teaching nexus. The University of Bristol has since aligned, moving from advocating a research-led approach (teaching the latest advancements in research) to being research-rich, and therefore encompassing all four quadrants.

Healey considers the various roles students and teachers can occupy. On one hand, the nexus aligns with a traditional approach focused on the role of the teacher. Students are less active and more of an audience – they can still engage with research content, but the emphasis is more on transmission of knowledge (research-led) or teaching processes of knowledge construction (research-oriented). On the other hand, the nexus is student-focused, and involves them either in engaging actively with research content (research-tutored approach) or carrying out their own research (research-based).

Benefits for students: A research-rich approach moves away from the traditional teacher-focused approach, which sees students as recipients of knowledge, to a student-centred approach that develops students’ true potential as researchers in training and as partners. As demonstrated by Healey and Roberts in 2004 and Healey in 2005, the students’ learning experience is greatly enriched and enhanced through not only access to cutting-edge research but also active and innovative teaching methods such as inquiry-based learning. This contributes to increased intrinsic motivation and the development of key skills (critical thinking, research skills) that also enhance students’ employability as shown by Griffiths in 2004. The students, in this approach, become an integral part of the university community of practice and can contribute to society throughout their studies.

Benefits for staff: These approaches are an opportunity to bring together two key aspects of colleagues’ professional lives – teaching and research – which might in turn lessen competing demands on time. Colleagues might share the research they are still developing with their students (whether through presenting the information or making students part of the exploration), with students acting as a sounding board. This can also provide an opportunity for staff to express their research to a general audience, receiving early feedback and an intake of fresh ideas. Looking at the experience of colleagues within the institution, other benefits mentioned are an opportunity to improve one’s teaching and job satisfaction, as cited by participants on the CREATE programmes. Finally, it is likely that among the students mentored through this research-rich experience is a future colleague and collaborator, who will have been inspired and empowered to pursue research and teaching.

Challenges of research-rich teaching

Time: Whilst colleagues might already include activities which sit across the different quadrants of Healey’s research-teaching nexus, in an environment in which demands on time and resource are ever-increasing and competing, it can be challenging to find the time and capacity needed to embed research-rich approaches in our teaching. In the first instance, it takes time and space to develop our own research interests and methodologies, and then to engage in (primary or secondary) research that might later be drawn upon in teaching. Subsequently, energy and expertise are required to review and develop our curricula and assessments to embed newly developed research-rich approaches. The resulting competition for time and resources often concludes with colleagues adopting a pragmatic response, in which curriculum enhancements are small and incremental, putting off more substantial development for a later date.

Conflict: The idea of competition between research and teaching extends into wider questions about the nature and purpose of universities, and the value placed upon our core activities. As Bage argued in 2018, “Universities typically value academics’ research over teaching, as indicators through which to judge career advancement and institutional prestige” (p.151). Whilst teaching and research are linked in our Vision and Strategy, how far might the organisation of academic staff at Bristol across three pathways, which separates and delineates research and/or teaching responsibilities, reinforce the distinctive nature of these activities?

Assessment: Assessment on programmes that adopt research-rich approaches might also be challenging (yet beneficial!), as these approaches often aim to develop multiple skillsets in our students including problem-solving skills, research skills, and subject specific knowledge. This can make it difficult (but not impossible) to design assessments that capture the full range of deep learning that results from research-rich approaches. To capture this range of learning, assessment of research-rich learning might involve portfolios, presentations, research projects and reports, or peer review, which can be more time-consuming for staff new to these approaches to mark and provide feedback on. This challenge might equally be seen as a benefit, however, as qualitative assessment is already a feature of many of our programmes, and we know that both staff and students gain much from assessments that promote deeper learning and engagement.

Research-rich teaching at the University of Bristol

Disciplinary approaches: Research-rich teaching at Bristol takes many forms. Beyond the institution’s historical research-led approach, we can also find many examples of innovative approaches covering Healey’s quadrants. One fantastic case study can be found in the Faculty of Health Sciences, bringing together first-year undergraduate dental and medical students to be part of a conference designed to assess their knowledge in only their 10th week at the University. This project demonstrates how students can experience being a researcher very early on. Students develop self-management, transferable skills and creativity through group work and inspiring tasks: an oral PechaKucha, a poster and a creative piece. If you are interested in reading more examples (or sharing your own), please visit the BILT blog page dedicated to research-rich teaching.

Research-rich Learning Communities: Research is not limited to being discipline-specific, and the University counts a great number of Scholarship of Learning and Teaching communities which bring together passionate colleagues, often Pathway 3, but not exclusively. The Engineering Education Research Group is an excellent example of colleagues from various pathways coming together to “lead and define a direction for engineering education and to encourage evidence-based pedagogical innovation both inside and outside the University of Bristol.” You can find their key research themes, publications and blog on their webpage linked to above.

Staff and students as partners: The Bristol Institute for Learning and Teaching (BILT) also champions research-rich teaching through investing in staff and students as partners. Colleagues can work on an existing BILT project or benefit from funding to work on their own project as it aligns with at least one BILT theme. The Student Research Journal and the Student Research Festival are student-led through the BILT student fellows who can count on the support and expertise of BILT colleagues. The former is an opportunity for students to get their outstanding work published in an online, peer-reviewed journal. The latter promotes and recognises the excellent research conducted by both undergraduate and postgraduate students, grouped around key themes.

Conclusion

Research-rich approaches to learning and teaching at Bristol thus have proven benefits for both our students and staff which can enrich the wider University and positively impact the world around us. But bringing together research and teaching remains challenging, and there is still a way to go to meet the aims set out in our University Vision. Whilst structural limitations might still impede our bringing together of research and teaching in our practice in the short term, as highlighted by Hordósy & McLean in 2022, in the longer term we must strive to develop a more equitable, inclusive, flexible and collaborative environment in which research and teaching are mutually encouraged and nurtured.

1 thought on “Research-rich teaching at the University of Bristol”