By Professor Marcus Munafò

Marcus is Associate Pro Vice-Chancellor of Research Culture at the University of Bristol. He leads on research culture activity across the university, providing direction and vision, working across the institutional landscape, and identifying key challenges and opportunities. He is also institutional lead for the UK Reproducibility Network.

Marcus is Associate Pro Vice-Chancellor of Research Culture at the University of Bristol. He leads on research culture activity across the university, providing direction and vision, working across the institutional landscape, and identifying key challenges and opportunities. He is also institutional lead for the UK Reproducibility Network.

Last month we welcomed colleagues from across the University to the Bristol Beacon’s Lantern Hall to learn more about the Working Well Together resource, as part of this year’s Enhancing Research Culture event series.

So, what is Working Well Together?

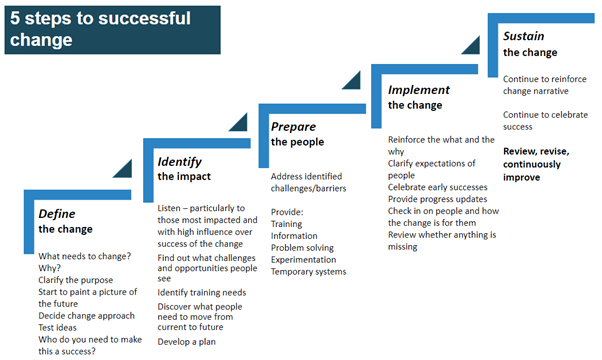

The Working Well Together (WWT) resource is designed to support teams, and the people within them, who work effectively in an HE context and enhance their team culture. It helps to create an environment in which everyone can thrive, and which enables high quality, reproducible research. The approach is inquisitive, starting with where teams are, identifying approaches which are right for them, and continuing to ask questions along the way.

The resource is designed to help teams do more of what they are doing well, and to support them in areas that are more challenging. It focuses on identifying some quick wins, but offers no quick fixes. The aim of the resource is to offer groups the tools and expertise to develop a culture that can help its members respond to the evolving challenges of their work.

Groups that have used the resource have found it an enjoyable way to take stock of how things are going, and start some of the harder conversations they need to have. They say it’s given insights into challenges they weren’t aware of, and helped remind them of what is going well and how to do more of the things that have a positive impact. Others have found it has equipped them with the skills needed to work well together, and started the process of making time to reflect and review as a group.

Teams / groups are invited to pilot the resource until the end of January 2025. When we talk about teams / groups this can include anyone who is part of, and supports, research activity, so may include academic staff, technical staff, professional services staff and research students. If you are interested in learning more about a pilot, please complete this form.

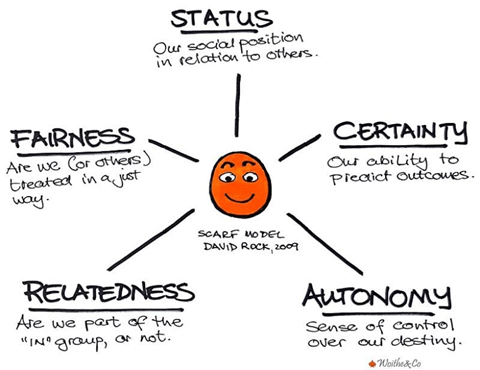

The WWT resource is about building stronger, more supportive teams in order to work more effectively together and create a more inclusive working environment.

From the Enhancing Research Culture allocated we receive from Research England, to the new People, Culture and Environment (PCE) assessment category in the next Research Excellence Framework (REF) assessment, it is clear that the organisations that shape the higher education system are emphasising the importance of a robust, equitable and inclusive research process from start to finish, rather than focusing solely the outputs of our research.

Panel discussion and Q+A: Looking ahead to REF 2029

To delve into this new REF category and what it means for the research landscape, I was joined by Dr Helen Young (Associate Director of Research Excellence, University of Bristol), Dr Caroline Jarrett (Faculty of Science and Engineering Technical Manager, University of Bristol) and Dr Faith Uwadiae (Research Culture and Communities Specialist, Wellcome Trust).

Over the course of an hour’s discussion we covered a lot, but some key points and highlights are summarised below;

- There was recognition from both academic and technical colleagues in attendance that the culture within research is improving, but there is still a long way to go

- Funders are already considering, and in some cases requiring, grant applications to consider people, the environment they work within, and the culture they create.

- The REF measures research outputs, which are naturally downstream from the work involved in setting up research or project teams, and carrying out the work.

- Positive changes to how we approach project setup and delivery therefore have an impact on our research outputs.

- Investing time and energy in building strong groups and ways of working pays dividends down the line, but currently this time and focus is often not prioritised.

The move to include People, Culture and Environment in REF2029 highlights the importance of the work that we have been doing both at an institutional level and within our own professional circles and teams to improve our research culture, and I thank all of you who have been involved over the years.

I’m reminded of a quote from one of our first ever Research Culture events, the talk on The Joy of Failure with Annie Vernon, who won Olympic silver in the Women’s Quadruple Sculls at Beijing 2008. Success doesn’t mean we did everything right, and failure doesn’t mean we did everything wrong. Together, we can continue to build on our success whilst recognising there are still areas to improve.