By Professor Tansy Jessop (PVC Education and Students (biography available online) and Paula Coonerty (Executive Director for Education and Students)

Introduction

In 2023, the APVC for Research Culture, Professor Marcus Munafo, initiated an internal review into teaching bureaucracy, following on from the internal review into research bureaucracy.

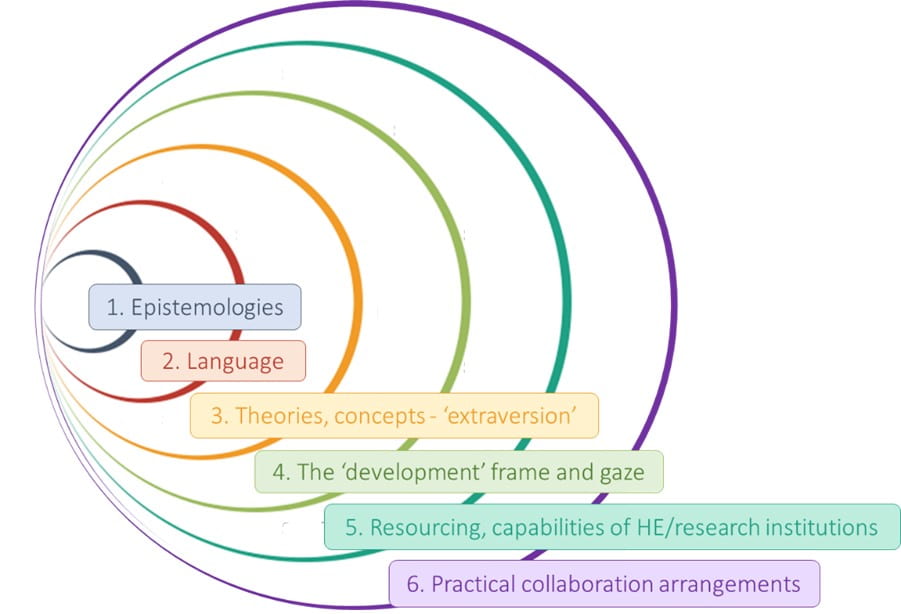

Within an organisation as large and complex as the University, a certain level of bureaucracy is necessary to ensure that we have timetables that don’t clash, students are registered on the right units, and well-qualified academics deliver teaching. In contrast to ‘necessary’ bureaucracy, this review focused on staff views of excessive, overly complicated, and hierarchical systems and processes.

Listening

Between February and March 2023, external consultants ran discussion sessions that were open to all staff (academic and professional services) involved in teaching activity. The purpose was to understand their experiences, identify pain points and see what works well. The sessions were advertised in the Staff Bulletin and the Education Bulletin. A total of 55 staff attended small focus group sessions (ten in total). Most participants (87%) were Pathway 1 or 3 teaching staff, and all three faculties were represented.

In analysing the results from the sessions, the consultants commended the ‘passion and dedication that the participants had for their teaching’, which is something we don’t take for granted. Our recent Silver award in TEF 2023 would not have been possible without incredibly dedicated staff delivering inspiring teaching and an outstanding student experience. So, what is getting in the way that we can improve?

Learning

The findings from the review are based on a small sample size, but many of the common themes replicate feedback provided via other routes (e.g. the research bureaucracy review, the Staff Voice workshops held in 2023, network forums, and anecdotal reports about staff experience).

Pain points

- General process and system inefficiencies. An increase over the years in bureaucracy, complex processes, and inefficient, outdated systems.

- Standardisation and the ‘one size fits all’ perception. Participants felt that standardization was stifling creativity and ignoring local context.

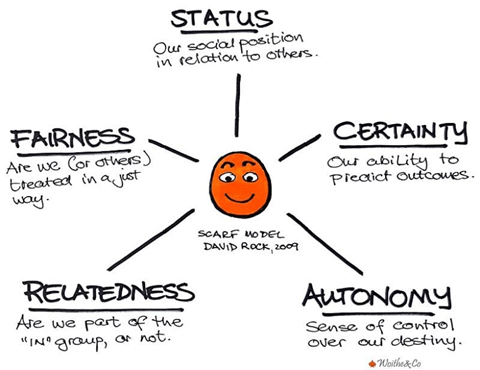

- Culture of compliance. More emphasis placed on compliance and less on local innovation and autonomy.

- Challenges when processes operate at scale. Processes and IT systems are no longer fit-for-purpose in a context of growing student numbers.

- Volume of change. The volume of change adds to workload and detracts from the core business of teaching and enhancing the student experience. Plus staff feel disconnected from large change programmes and the drivers for change are often unclear.

- Changing nature of the student body. Increasing numbers of international students and students with additional support entails workload challenges.

- Teaching standards and high-quality teaching. Staff feel there is more focus on metrics (such as the NSS) than on high-quality teaching. Alongside this, Bristol is seen as valuing research over teaching.

Examples of good practice

- Expert support provided by highly skilled, knowledgeable professional services staff who are eager to help.

- Individual roles and teams dedicated to supporting innovation.

- Transformational system and process changes delivered by the Education Administration Enhancement project.

The full report is available on SharePoint (UoB staff access only).

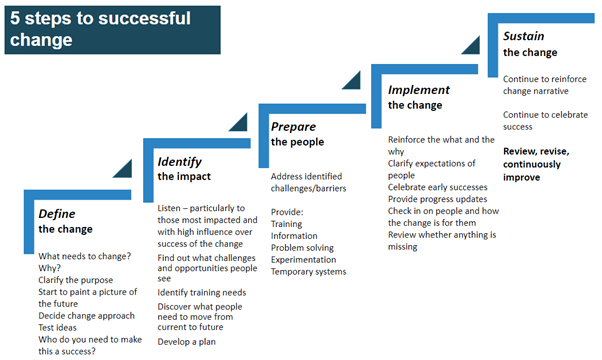

Acting

Systems

Here are some of the changes we are making:

- Qwickly has been decommissioned and replaced with a new Check-In app and system for monitoring student attendance.

- Blackboard is being upgraded to Blackboard Ultra, which includes many new and improved features.

- The Education Administration Enhancement (EAE) project focuses on continuous improvements to systems relating to finance, education, admissions and recruitment (e.g. eVision). For example, from 2023/24 live information about Study Support Plans (SSPs) is available in eVision for personal tutors and unit directors to review.

- UPMS was identified as a pain point in the review, but there are currently no plans to change this system as a new curriculum management system would require significant investment, integration costs, and large-scale institutional change.

Workload

There are several initiatives in train that in the long-term will help manage workload, but in the short-term require staff time and effort to make changes.

- The new Structure of the Academic Year (SAY) is designed to help contain workloads and support student and staff wellbeing. However, we know that in the short-term, SAY changes are time costly and entail extra work for many staff.

- TB1 assessments will take place before Christmas with a dedicated marking week before the start of TB2, and staff will be able to start teaching in TB2 without marking hanging over them. Students should receive their feedback before they start their new units too.

- Reassessment activity has been brought forward to create more space during the summer for staff to concentrate on research and take annual leave. This will also ensure the period at the end of the summer vacation is less intense. As part of the new SAY, we are also introducing streamlined Examination Boards, thereby reducing duplication and multiple touchpoints.

- High assessment loads (and associated high workload for staff) go against the integrated and inclusive principles of our Assessment and Feedback Strategy. In 2023 we held workshops with schools to support reductions in summative assessment load, balanced by more engaging formative assessment and feedback.

- In some larger schools, different personal tutoring models are being piloted (e.g. placing some of the student support functions provided by personal tutors with professional services staff) and the results are feeding into the Professional Services Transformation Programme (PSTP) (see ‘next steps’).

Communication

Our fortnightly Education Bulletin, introduced during Covid-19, is our main regular communication channel about education. In addition, the Bristol Institute for Learning and Teaching (BILT) releases a fortnightly briefing full of inspiring, thoughtful and exciting practices and ideas from colleagues. We also have dedicated communication channels for special projects. Our new SharePoint site for the upgrade to Blackboard Ultra is where you will be able to find latest updates. Similarly, the University Structures programme has a SharePoint site, as does the SAY project where you can find information about these change projects.

We heard from the Teaching Bureaucracy Review that we need to be better at communicating when work is paused, or only limited progress is being made. When there is a communications vacuum this creates space for uncertainty and staff feel they are being kept out of the loop. We will learn from this and share this finding with teams leading education-related projects.

Consultation and engagement

We are continuing to listen to staff and introducing new ways for you to provide feedback.

Since 2020 we have introduced networks to provide space for staff in similar roles to connect, discuss common challenges and share good practice. We now have networks for School Education Directors, Senior Tutors, Academic Integrity Officers, Student Disability Coordinators, Student Administration Managers and Graduate Administration Managers. In January 2024 we launched a new Student Academic Representation Network which brings together staff and students involved in Student Staff Liaison Committees (SSLCs).

From spring 2024 a new Admissions and Recruitment Committee has been convened to connect Faculty Admissions Officers with central staff in Admissions.

As part of upgrading to Blackboard Ultra, we are establishing a project advisory group. We will be seeking members from across the University, to ensure your voices are feeding into the implementation plan.

At the time of writing this, the 2024 Staff Experience Survey has just closed and we look forward to reviewing any feedback from that survey which relates to your experience of teaching and education.

Next steps

While this blog provides a flavour of some of the changes we are currently making, the detailed findings of the teaching bureaucracy report have been passed onto relevant teams and leaders to consider.

We welcome the time staff took to attend the discussion sessions and the final report is a fantastic source of evidence for the PSTP. The PSTP launched in 2023 and its purpose is to review and transform how we deliver services, reducing bureaucracy and improving ways of working. Education and student support services has been identified as a priority focus for the PSTP, with areas such as assessment processes, provision of information, and student wellbeing support identified as important. This work picks up on pain points raised via the teaching bureaucracy review).

You can find more information online about the PSTP.